Last week I was discussing the use of DL/VA to differentiate between the different causes of gas exchange defects with a physician. DL/VA is DLCO divided by the alveolar volume (VA). It is an often misunderstood value and the most frequent misconception is that it is a way to determine the amount of diffusing capacity per unit of lung volume (and therefore a way to “adjust” DLCO for lung volume). This is not the case because dividing DLCO by VA actually cancels VA out of the DLCO calculation and for this reason it is actually an index of the rate at which carbon monoxide disappears during breath-holding.

[Note: The value calculated from DLCO/VA is related to Krogh’s constant, K, and for this reason DL/VA is also known as KCO. The term DL/VA is misleading since the presence of ‘VA’ implies that DL/VA is related to a lung volume when in fact there is no volume involved. The use of the term DL/VA is probably a major contributor to the confusion surrounding this subject and for this reason it really should be banned and KCO substituted instead.]

I’ve written on this subject previously but based on several conversations I’ve had since then I don’t think the basic concepts are as clear as they should be.

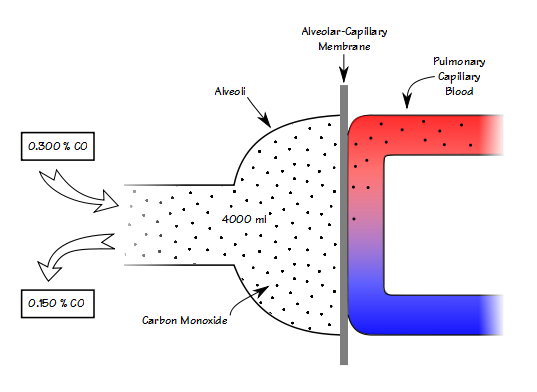

When you know the volume of the lung that you’re measuring, then knowing the breath-holding time and the inspired and expired carbon monoxide concentrations allows you to calculate DLCO in ml/min/mmHg. When you remove the volume of the lung from the equation however (which is what happens when you divide DLCO by VA), all you can measure is how quickly carbon monoxide decreases during breath-holding (KCO).

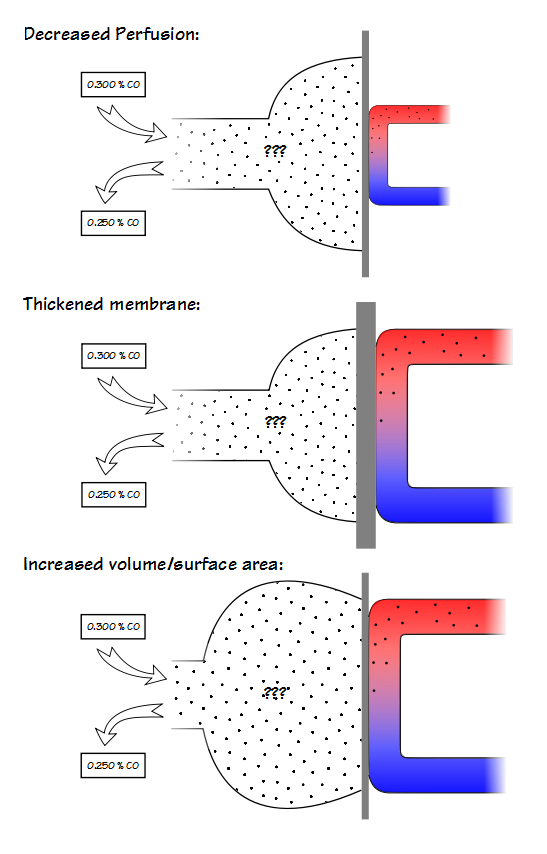

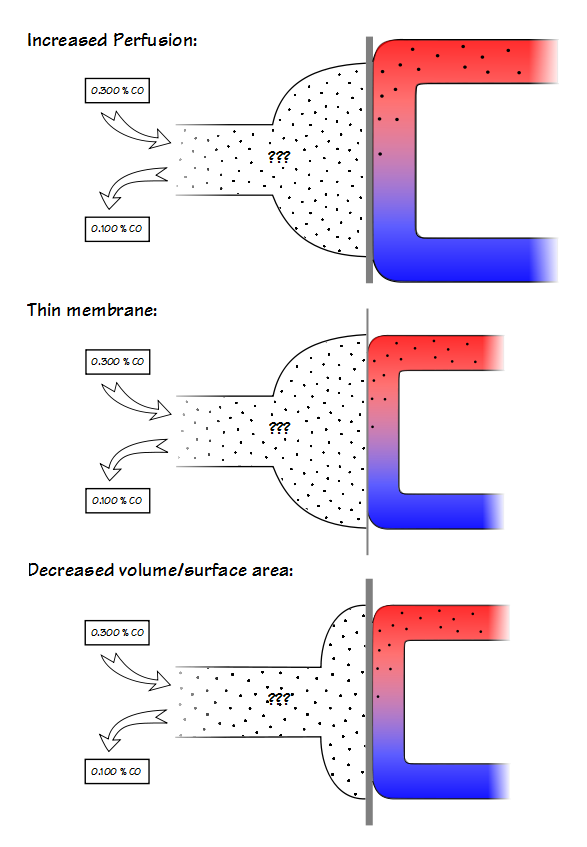

A low KCO can be due to decreased perfusion, a thickened alveolar-capillary membrane or an increased volume relative to the surface area.

A high KCO can be due to increased perfusion, a thinner alveolar-capillary membrane or by a decreased volume relative to the surface area. Because it is not possible to determine the reason for either a low or a high KCO this places a significant limitation on its usefulness.

This doesn’t mean that KCO cannot be used to interpret DLCO results, but its limitations need to recognized and the first of these is that the rules for using it are somewhat different for restrictive and obstructive lung diseases.

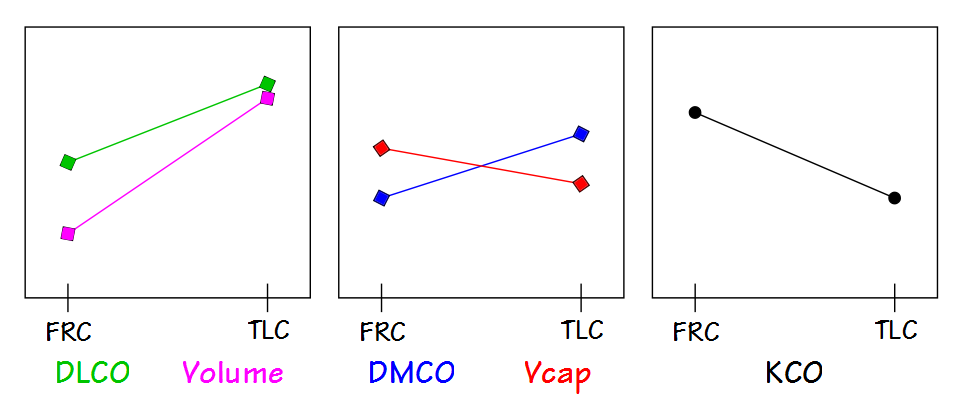

KCO is probably most useful for assessing restrictive lung diseases and much that has been written about KCO is in reference to them. The basic idea is that for an otherwise normal lung when the TLC is reduced DLCO also decreases, but does not decrease as fast as lung volume decreases. Part of the reason for this is that surface area does not decrease at the same rate as lung volume. This by itself would be a simple reason for KCO to increase as lung volume decreases but the complete picture is a bit more complicated.

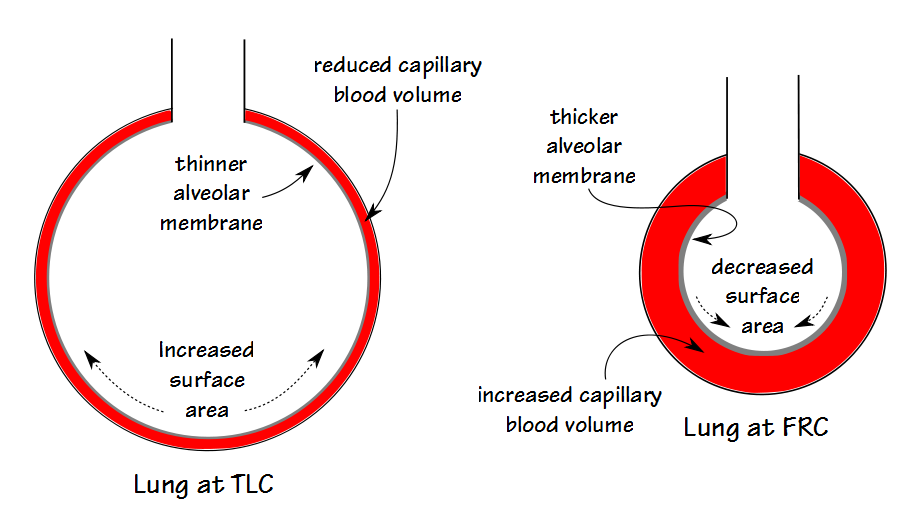

The lung reaches its maximum surface area near TLC, and this is also when DLCO is at its maximum. At this time the alveolar membrane is stretched and at its thinnest which reduces the resistance to the transport of gases across the membrane. Simultaneously however, the pulmonary capillaries are also stretched and narrowed and the pulmonary capillary blood volume is at its lowest.

As lung volume decreases towards FRC, the alveolar membrane thickens which increases the resistance to gas transport but this is more than counterbalanced by an increase in pulmonary capillary blood volume. When factored in with a decrease in alveolar volume (which decreases the amount of CO available to be transferred), the rate at which CO decreases during breath-holding (for which KCO is an index) increases.

This means that when TLC is reduced but the lung tissue is normal, which would be the case with neuromuscular diseases or chest wall diseases, then KCO should be increased. There is no particular consensus about what constitutes an elevated KCO however, and although the amount of increase is somewhat dependent on the decrease in TLC, it is not predictable on an individual basis. For this reason, in my lab a KCO has to be at least 120 percent of predicted to be considered elevated (and I usually like it to be above 130% to be sufficiently confident).

Interstitial involvement in restrictive lung disease is often complicated and there can be multiple reasons for a decrease in DLCO. Scarring and a loss of elasticity causes the lung to become stiffer and harder to expand which decreases TLC. The alveolar membrane can thicken which increases the resistance to the transfer of gases. And probably most commonly there is destruction of the alveolar-capillary bed which decreases the pulmonary capillary blood volume and the functional alveolar-capillary surface area.

This means that when TLC is reduced and there is interstitial involvement, a normal KCO (in terms of percent predicted) is actually abnormal. A normal KCO can be taken as an indication that the interstitial disease is not as severe as it would considered to be if the KCO was reduced, but it is still abnormal.

KCO has a more limited value when assessing reduced DLCO results for obstructive lung disease. This is because the TLC is more or less normal in obstructive lung diseases and it is the DLCO, not the KCO, that is the primary way to differentiate between a primarily airways disease like asthma and one that also involves the lung tissue like emphysema. Strictly speaking, when TLC is normal and the DLCO is reduced, then KCO will also be reduced.

VA is a critical part of the DLCO equation however, so if VA is reduced because of a suboptimal inspired volume (i.e. inhalation to a lung volume below TLC), then DLCO may be underestimated. In this specific situation, if the lung itself is normal, then KCO should be elevated. When significant obstructive airways disease is present however, VA is often reduced because of ventilation inhomogeneity. This can be assessed by calculating the VA/TLC ratio from a DLCO test that was performed with acceptable quality (i.e. good inspired volume). A low VA/TLC ratio (less than 0.85) indicates that a significant ventilation inhomogeneity is likely present.

Does a low VA/TLC ratio make a difference when interpreting a low DLCO? Not really, but it brings up an interesting point and that is that the VA/TLC ratio indicates how much of the lung actually received the DLCO test gas mixture (at least for the purposes of the DLCO calculation). It also indicates that the DLCO result only applies to that fraction of the lung included within the VA/TLC ratio. Does that mean that the DLCO is underestimated when the VA/TLC ratio is low? The answer is maybe, but probably not by much.

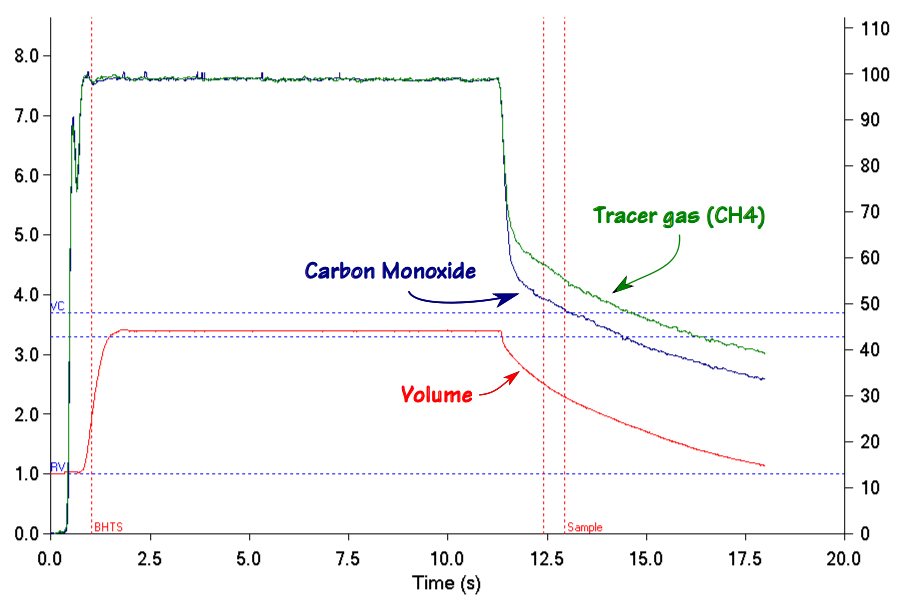

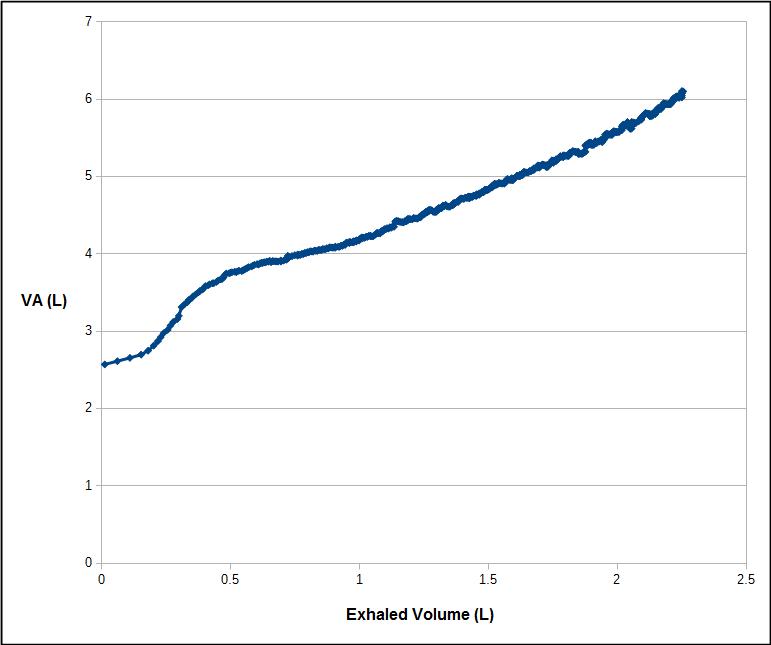

It is important to remember that the VA is measured from an expiratory sample that is optimized for measuring DLCO, not VA. When an individual with significant ventilation inhomogeneity exhales, the tracer gas (and carbon monoxide) concentrations are highest at the beginning of the alveolar plateau and decrease throughout the remaining exhalation.

The calculated VA therefore depends on where the tracer gas is measured during exhalation.

To one degree or another a reduced VA/TLC ratio is an artifact of the DLCO measurement requirements. At least one study has indicated that when the entire exhalation is used to calculate DLCO both healthy patients and those with COPD have a somewhat higher DLCO (although I have reservations about the study’s methodology). For the COPD patients at least part of the improvement was due to an increase in the measured VA. But the fact is that for regular DLCO testing any “missing” fraction isn’t measured so it really isn’t possible to say what contribution it would have made to the overall DLCO.

In general a low KCO is usually seen in:

- Interstitial disease

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome

- Emphysema

- Bronchiolitis

An elevated KCO is usually seen in:

- Pneumonectomy

- Neuromuscular disease

- Chest wall disease

- Alveolar hemorrhage

- Asthma

- Obesity

More than one study has cast doubt on the ability of KCO to add anything meaningful to the assessment of DLCO results. Despite this KCO has the potential be useful but it must be remembered that it is only a measurement of how fast carbon monoxide disappears during breath-holding. KCO can be reduced or elevated due to differences in alveolar membrane thickness, pulmonary blood volume as well as lung volume but it cannot differentiate between these factors, and the best that anyone can do is to make an educated guess. Realistically, the diagnosis of a reduced DLCO cannot proceed in isolation and a complete assessment requires spirometry and lung volume measurements as well.

In addition, there is an implicit assumption is that DLCO was normal to begin with. This is not necessarily true and as an example DLCO is often elevated in obesity and asthma for reasons that are unclear but may include better perfusion of the lung apices and increased perfusion of the airways. These individuals have an elevated KCO to begin with and this may skew any changes that occur due to the progression of restrictive or obstructive lung disease.

Finally DLCO tests have to meet the ATS/ERS quality standards for the KCO to be of any use and what we consider to be normal or abnormal about DLCO, VA and KCO depends a lot on the reference equations we select.

References:

Aduen JF et al. Retrospective study of pulmonary function tests in patients presenting with isolated reductions in single-breath diffusion capacity: Implications for the diagnosis of combined obstructive and restrictive lung diease. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82(1): 48-54.

Cotes JE, Chinn DJ, Miller MR. Lung Function. Physiology, measurement and application in medicine. 2006, Blackwell Publishing.

Frans A, Nemery B, Veriter C, Lacquet L, Francis C. Effect of alveolar volume on the interpretation of single-breath DLCO. Respir Med 1997; 91: 263-273.

Hansen JE. Pulmonary function testing and interpretation. 2011, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, Ltd,

Horstman MJM, Health B, Mertens FW, Schotborg D, Hoogsteden HC, Stam H. Comparison of total-breath and single-breath diffusing capacity if health volunteers and COPD patients. Chest 2007; 131: 237-244.

Hughes JMB, Pride NB. In defence of the carbon monoxide transfer coefficient KCO (TL/VA). Eur Respir J. 2001; 17: 168-174.

Hughes JMB, Pride NB. Examination of the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) in relation to its KCO and VA components. Amer J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186(2): 132-139.

Johnson DC. Importance of adjusting carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) and carbon monoxide transfer coefficient (KCO) for alveolar volume, Respir Med 2000; 94: 28-37.

Kaminsky DA, Whitman T, Callas PW. DLCO versus DLCO/VA as predictors of pulmonary gas exchange. Respir Med 2007; 101: 989-994.

Saydain Gm Beck KC, Decker PA, Cowl CT, Scanlon PD, Clinical significance of elevated diffusing capacity. Chest 2004; 125: 446-452.

van der Lee I, Zanen P, van den Bosch JMM, Lammers JWJ. Pattern of diffusion disturbance related to clinical diagnosis: The KCO has no diagnostic value next to the DLCO. Respir Med 2006; 100: 101-109.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License