Obesity has become far more commonplace than it was a generation ago. The reasons for this are unclear and have been attributed at one time or another to hormone-mimicking chemicals in our environment, altered gut biomes, sedentary lifestyles or the easy availability of high calorie foods. Whatever the cause, obesity affects lung function through a variety of mechanisms although not always in a predictable manner.

Spirometry:

Many investigators have shown a relatively linear relationship between an increase in BMI and decreases in FVC and FEV1. These decreases are small however, and FVC and FEV1 tend to remain within normal limits even in extreme obesity. The decreases in FEV1 and FVC tend to be symmetrical which is shown by the fact that the FEV1/FVC ratio is usually preserved in obese subjects without lung disease. Several studies have shown that the decreases in FVC and FEV1 are reversible since a decrease in weight showed a corresponding increase in FVC and FEV1.

In one study a 1 kg increase in weight correlated with a decrease in FEV1 of approximately 13 ml in males and 5 ml in females. The same increase in weight correlated with a decrease in FVC of approximately 21 ml in males and 6.5 ml in females. The greater change in FVC and FEV1 in males than females has been attributed to the fact that males tend to accumulate extra weight primarily in the abdomen.

The notion that abdominal weight has a disproportionate effect on lung function is seconded to some extent by studies that have shown that decreases in FVC and FEV1 correlated better with increases in waist circumference and the waist to hip ratio than with BMI. One study showed a 1 cm increase in waist circumference caused a 13 ml reduction in FVC and an 11 ml reduction in FEV1 across a range of elevated BMI’s.

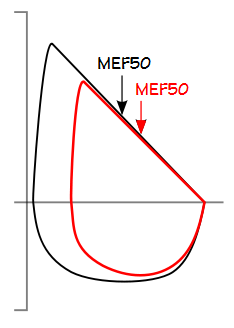

Expiratory and inspiratory flow rates (PEF, MEF50, PIF and MIF50) and MVV also decrease relatively linearly with increasing BMI, although for different reasons. Decreases in expiratory flows are most likely caused when a decreased FVC causes flows to move to a lower position on the maximal flow-volume curve. Inspiratory flow rates are limited by an increase in the mass that must be moved during inspiration.

Despite the increase in abdominal girth with increasing BMI there is no significant difference in FVC and FEV1 between sitting and standing.

Lung Volumes:

There is also a relatively linear association between an increase in BMI and decreases in TLC and RV, however they also usually remain within normal limits and the RV/TLC ratio is preserved even in morbidly obese individuals. FRC and ERV however, show exponential decreases with increasing BMI so that even mildly overweight individuals can show noticeable changes. Morbidly obese individuals frequently show a maximal decrease in ERV and FRC and in these individuals FRC is usually not significantly different from RV. These lung volume changes are attributed to the increased body mass which causes an extra loading on the thorax, marked increases the intra-abdominal pressure and impedes movement of the diaphragm. In general this means that RV tends to be preserved and FRC and ERV decrease as BMI increases. The changes in lung volumes are reversible since several studies have shown that when weight decreases TLC, FRC and ERV increase.

One study showed a 30 ml decrease in FRC per kilogram increase in weight for males and a 20 ml decrease in FRC per kilogram increase in females. The investigators attributed the difference between the genders to the fact that central (abdominal) obesity is more common in males than females and in fact several studies have shown that decreases in FRC and ERV correlate better with waist circumference and the waist to hip ratio (which tend to be lower in females) than they do to BMI.

FRC and ERV tends decrease even further in the supine position. Several investigators have shown that when this happens it is likely accompanied by an increase in regional gas trapping since the Closing Volume may exceed the ERV and occur above FRC in the supine position. This may be why many obese subjects report increased dyspnea in the supine position.

Although decreases in FVC, FEV1 and ERV are generally associated with obesity, determining the effect on a specific individual is often less precise. One study of obese individuals showed that individuals with a low MVV also tended to have larger decreases in FVC, FEV1, ERV, IC and TLC than did subjects with a normal MVV and that this did not correlate with BMI. Individuals with a low MVV also had lower inspiratory and expiratory flow rates, a decrease in respiratory muscle strength and a higher RV/TLC ratio. This pattern would seem to show that a decrease in MVV is a symptom, not a cause, of the difference in lung function between the two groups.

N2 washout time and helium wash-in time may be increased during lung volume measurements in obese subjects because of poor ventilation in the dependent lung units but this is primarily seen in patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome and a low PaO2. One study showed data indicating a slightly higher TLC measured by plethysmography than by helium dilution which was attributed to gas trapping. It’s unclear that this is the case since after weight loss the same study showed that plethysmographic TLC increased more than helium dilution TLC.

DLCO:

There is a great deal of conflicting evidence about obesity’s effect on DLCO. At least one retrospective study showed no significant correlation between BMI and either DLCO or KCO and another study showed no difference in DLCO before and after significant weight loss. Numerous other studies however, have shown that in individuals without evident lung disease DLCO was usually reduced in obesity and the decrease correlated with increasing BMI. Where noted this has been attributed this obesity related atelectasis.

Other investigators have shown that DLCO increases with increasing BMI. This has usually been attributed to an increased resting VO2 which causes an increased cardiac output and pulmonary capillary blood volume. In a large population study of individuals with an elevated DLCO there was a high correlation with an elevated BMI and another study showed that DLCO decreased during weight loss.

Regardless of whether they’ve shown that DLCO increases or decreases most investigators have noted an increase in DLCO/VA (KCO) that correlates with increasing obesity. The discrepancy between these different observations may be related to alveolar volume since one study noted that when alveolar volume was preserved DLCO tended to be elevated and when VA was decreased, DLCO was reduced. Another study noted that DLCO tended to be lower with increasing BMI in men than women and attributed this to women having a lower waist-to-hip ratio. This could well be the case, however the differences in DLCO based on waist-to-hip ratios in males has not been explored.

Exercise:

Numerous studies have shown that VO2, VCO2 and Ve are higher at rest in obese individuals than in those with a normal weight. VO2 and VCO2 are also higher for any given workload than for subjects with a normal body weight. The rate of increase in VO2 with increasing workload in obese subjects tends to be the same as for normal weight subjects but is shifted upwards which means that the maximum workload tends to be reduced and that maximum VO2 will be reached in a shorter period of time. Minute ventilation tends to increase faster with exercise in obese subjects which leads to an increased Ve/VO2 at any workload. The Ve-VCO2 slope however is usually normal. Anaerobic threshold usually occurs at a lower workload but the VO2 in LPM at AT is usually normal. Peak VO2 when expressed as ml/kg/min is usually reduced but in LPM it is also usually normal. SpO2 is usually normal.

Work of breathing:

The work of breathing increases with increasing body weight. This is attributed both to the increase in mass and to the fact that when FRC decreases, tidal breathing occurs at a less efficient portion of the pressure-volume curve of the lung. In addition when breathing at low lung volumes expiratory flow may encroach on the maximal flow volume loop envelope which increases the likelihood of expiratory flow limitation. Total respiratory compliance has been shown to decrease significantly and RAW to increase significantly during tidal breathing in obese subjects. The decrease in compliance has been primarily attributed to a decrease in chest-wall compliance from an increase in fat in and around the ribs, diaphragm and abdomen. The increase in RAW has been attributed to airway narrowing from an FRC that is closer to RV than in normal-weight subjects. These effects are reversible since several studies have shown that RAW decreases and SGaw increases after weight loss.

There is a relatively linear relationship between increases in RAW, decreases in SGaw and increases in BMI although these tend to be greater in males than in females. Like other lung function values this is attributed to a greater amount of abdominal obesity in males compared to females.

Asthma:

Although a number of studies have shown an association between asthma and obesity at least one study showed that even though wheezing increased with a longitudinal increase in body weight the presence of asthma as defined by an increase in FENO did not. This is seconded to some extent by the general finding that a decreased FEV1/FVC ratio is not associated with obesity and that a decrease in weight does not decrease airway reactivity as judged by methacholine responsiveness.

One study showed that obese asthmatics had a larger increase in FRC and ERV, and a larger decrease in IC during methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction than did individuals with a normal BMI. A closer look at their data however, showed that prior to bronchoconstriction their most obese cohort (BMI>30) had normal FRCs and elevated ERVs which is more than somewhat contrary to effects on lung volume that are usually associated with obesity. Other studies of obese asthmatics have shown the expected decreases in FRC and ERV so it is unclear the results from this study are actually representative.

COPD:

Interestingly, the effects of obesity tend to act in opposition to some of the effects from COPD. An elevated FRC and a reduced IC (hyperinflation) are frequent consequences of severe COPD and studies have shown that FRC and IC decreased with an increasing BMI compared to subjects with a normal body weight when the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio were the same.

Obesity also tends to counteract some of the effects of COPD during exercise. When compared to individuals with a normal weight individuals with COPD those with an elevated BMI had a lower TLC, a lower FRC and a higher IC. During exercise obese individuals with COPD were able to reach a higher maximum oxygen consumption and a higher Ve than their normal weight counterparts. Although at peak exercise both normal weight and obese individuals had similar levels of dynamic hyperinflation, this occurred at a significantly higher minute ventilation for the obese individuals.

Reference equations:

Although it is clear that obesity affects lung function body weight, BMI, BSA, waist circumference and waist to hip ratios are almost never factors in reference equations. In fact, studies often indicate that weight was not a statistically significant factor. This is likely due to the in which study populations are selected. Obese individuals are often excluded either explicitly or because they often have co-morbid factors. For this reason, despite the fact that obesity has become commonplace reference equations are usually based on a population with relatively normal body weights.

An interesting question would be whether reference equations should be re-factored to include a wider range of body weights. I don’t think they should and part of the reason for this is that when the effects of obesity are determined for a group the relationship between BMI and the value being studied are often statistically relevant but extending this relevance to a specific individual has frequently been shown to be problematic. Another reason is that even though it is possible to be overweight and healthy, obesity is not the normal default condition for humans and if reference equations include weight as a factor then results that should probably be considered abnormal may instead look normal.

Pulmonary function testing can be more challenging when the patient is obese. Patient chairs and wheelchairs may be tight and uncomfortable, plethysmographs may be too small and dyspnea can prevent the patient from cooperating fully with testing directions. Since obesity is encountered so frequently however, accommodations for these factors should be routine for any pulmonary function lab.

When pulmonary function reports are reviewed from an individual with an elevated BMI the FVC, FEV1, TLC, RV and DLCO are likely going to be within normal limits until obesity is extreme. This says something about the resilience of the human body but it also isn’t the same as saying there is no effect. Obese individuals are far more likely to complain of dyspnea. Sleep apnea, cor pulmonale, orthopnea, hypoxia and hypercapnia are some of the potential pulmonary consequences of obesity. Obesity can also exacerbate existing cardiovascular, pulmonary and metabolic disorders. The effects of obesity are not necessarily predictable however, and individuals with the same gender, age, height and BMI may can have substantially different pulmonary function results. Part of this may be due to differences in factors like waist circumference and waist to hip ratios but co-morbid conditions likely factor in this as well.

Since a decreased ERV is a relatively accurate indicator of the effect obesity has on lung volumes more than one investigator has proposed that the ERV and ERV/VC ratio can be obtained from just a Slow Vital Capacity maneuver. This is a simple and cost effective way of monitoring lung function and another reason that slow vital capacities should be performed as part of routine spirometry more often

References:

Aaron SD, Fergusson D, Dent R, Chen Y, Vandemheen KL, Dales RE. Effect of weight reduction on respiratory function and airway reactivity in obese women. Chest 2004; 125: 2046-2052.

Babb TG, Wyrick BL. DeLorey DS, Chase PJ, Feng MY. Fat distribution and end-expiratory lung volume in lean and obese men and women. Chest 2008; 134: 704-711.

Chen Y, Rennie D, Cormier YF, Dosman J. Waist cirumferance is associated with pulmonary function in normal-weight, overweight and obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 85: 35-39.

Collard P, Wilputte J-Y, Aubert G, Rodenstein DO, Frans A. The single-breath diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide in obstructive sleep apnea and obesity. Chest 1996; 110: 1189-1193.

Dagher HN, Bartter T, Kass J, Pratter MR. The effect of obesity on Diffusing Capacity (DLCO) and the Diffusing Capacity adjusted for alveolar volume (DL/VA). Chest 2004; 126: 799S.

DeJong, AT, Gallagher MJ, Sandberg KR, Lillystone MA, Spring T, Franklin BA, McCullough PA. Peak oxygen consumption and the minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production relation slope in morbidly obese men and women: influence of subject effort and body mass index. Prev Cardiol 2008; 11: 100-105.

Enach I, Oswald-Mammosser M, Scarfone S, Simon C, Schlienger J-L, Geny B, Charloux A. Impact of altered alveolar volume on the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide in obesity. Respiration 2011; 81: 217-222.

Fenger RV, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Vidal C, Husemoen L-L, Skaaby T, Thueson BH, Madsen F, Linneberg A. The longitudinal relationship of adiposity to changes in pulmonary function and risk of asthma in a general adult population. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2014; 14: 208.

Gudmundsson G, Cerveny M, Shasby DM. Spirometric values in obese individuals. Effects of body position. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156: 998-999

Hakala K, Stenius-Aarniala B, Sovijarvi A. Effects of weight loss on peak flow variability, airways obstruction, and lung volume in obese subjects with Asthma. Chest 2000; 118: 1315-1321.

Hansen JE. Pulmonary function testing and interpretation. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, 1911.

Hoskote SS, Iakovou A, Colaco CG, Patel VP, Gerolemou L, Eden E, Chacana A. Effect of obesity on diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide: A retrospective analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187: A1925.

Jones RL, Nzekwu M-MU. The effects of body mass index on lung volumes. Chest 2006; 130: 827-833.

King GG, Brown NJ, Diba C, Thorpe CW, Munoz P, Marks GB, Toelle B, Ng K, Berend N, Salome CM. The effects of body weight on airway caliber. Eur Respir J 2005; 25: 896-891.

Ladosky W, Botelho MAM, Albuquerque JP. Chest mechanics in morbidly obese non-hypoventilated patients. Respir Med 2001; 95: 281-286.

Luce JM. Respiratory complications of obesity. Chest 1980; 78: 627-631.

O’Donnell DE, Deesomchok A, Lam Y-M, Guenette JA, Amornputtisathaporn N, Forkert L, Webb KA. Effects of BMI on static lung volumes in patients with airway obstruction. Chest 2011; 140(2): 461-468.

Ora J, Laveneziana P, Ofir D, Deesomchok A, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE. Combined effects of obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in dyspnea and exercise. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180: 964-971.

Pekkarinen E, Vanninen E, Lansimies E, Kokkarinen J, Timonen KL. Relation between body composition, abdominal obesity and lung function. Clin Physiol Func Imaging 2012; 32: 83-88.

Sahebjami H, Gartside PS. Pulmonary function in obese subjects with a normal FEV1/FVC ratio. Chest 1996; 110: 1425-1429.

Salvadori A, Fanari P, Mazza P, Agosti R, Longhini E. Work capacity and cardiopulmonary adaptation of the obese subject during exercise testing. Chest 1992; 101: 674-679.

Salome CM, King GG, Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol 2010; 108: 206-211.

Santana ANC, Souza R, Martins AP, Macedo F, Rascovski A, Salge JM. The effect of massive weight loss on pulmonary function of morbid obese patients. Respir Med 2006; 100: 1100-1104.

Saydain G, Beck KC, Decker PA, Cowl CT, Scanlon PD. Clinical significance of elevated diffusing capacity. Chest 2004; 125: 446-452.

Steir J, Lunt A, Hart N, Polkey MI, Moxham J. Observational study of the effect of obesity on lung volumes. Thorax 2014; 69: 752-759.

Sutherland TJT, Cowan JO, Taylor DR. Dynamic hyperinflation with bronchoconstriction. Differences between obese and nonobese women with asthma. Am J Respi Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 970-975.

Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Stringer WW, Whipp BJ. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation, Fourth edition. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

Zahir M, Sharma P, Eneh K, Patolia S, Vadde R, Schmidt MF. Correlation of body mass index (BMI) with the diffusing capacity (DLCO) and the diffusing capacity adjusted for alveolar volume (DLCO/VA) in overweight adults: a retrospective analysis. Chest 2009; 136(4): 120S.

Zavorosky GS, Christou NV, Kim DJ, Carli F, Mayo NE. Preoperative gender difference in pulmonary gas exchange in morbidly obese subjects. Obes Surg 2008; 18: 1587-1598.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License