When I review the results from a CPET I am used to considering a maximum minute ventilation (Ve) greater than 85% of predicted as an indication of a pulmonary mechanical limitation. Recently a CPET report came across my desk with a maximum minute ventilation that was 142% of predicted. How is this possible and does it indicate a pulmonary mechanical limitation or not?

It is unusual to see a Ve that is greater than 100% of predicted. We derive our predicted max Ve from baseline spirometry and calculate it using FEV1 x 40. We have tried performing pre-exercise MVV tests in the past and using the maximum observed MVV as the predicted maximum Ve but our experience with this has been poor. Patients often have difficulty performing the MVV test correctly and realistically even if it is performed well the breathing maneuver used during an MVV test is not the same as what occurs during exercise. Since both Wasserman and the ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing recommend the use of FEV1 x 35 or FEV1 x 40 as the predicted maximum minute ventilation we no longer use the MVV.

There are usually only two situations where a patient’s exercise Ve is greater than their predicted max Ve. First, when a patient is severely obstructed their FEV1 is quite low and FEV1 x 40 may underestimate what they are capable of since they are occasionally able to reach a Ve a couple of liters per minute higher than we expected. Second, if the FEV1 is underestimated due to poor test quality then the predicted max Ve will also be underestimated. In this case however, the baseline spirometry had good quality, was repeatable and the results did not show severe obstruction but instead looked more like mild restriction.

| Effort 1: | Effort 2: | Effort 3: | |

| FVC (L): | 2.51 | 2.52 | 2.60 |

| FEV1 (L): | 1.86 | 1.87 | 1.95 |

| FEV1/FVC %: | 74 | 74 | 75 |

| PEF: | 6.26 | 6.46 | 6.37 |

The patient’s TLC had been 70% of predicted when measured a month previously. Despite this and the somewhat restrictive looking spirometry, the diagnosis we had been given for the CPET was Asthma. One of the more common effects that exercise usually has on an individual with asthma is Exercise Induced Bronchoconstriction (EIB). This is one of the primary reasons that we routinely perform pre- and post-exercise spirometry as part of our CPETs. Most people usually have a small increase (3%-5%) in their FEV1 following exercise. When we see a significant decrease in FEV1 (greater than 12%) following exercise we usually consider EIB to be the cause. A small number of asthmatics however, do not bronchoconstrict with exercise, they bronchodilate, and that is what this patient did.

| Pre-Exercise: | %Predicted: | Predicted: | Post-Exercise: | %Predicted: | %Change: | |

| FVC (L): | 2.60 | 57% | 4.57 | 3.02 | 66% | +16% |

| FEV1 (L): | 1.95 | 54% | 3.59 | 2.30 | 64% | +18% |

| FEV1/FVC%: | 75 | 95% | 78 | 76 | 97% | +2% |

The patient was actually rather physically fit and other than their Ve had an above-average exercise test.

| AT | %Predicted: | Peak | %Predicted: | |

| VO2 (LPM): | 1.63 | 64% | 3.01 | 118% |

| VO2 (ml/kg): | 21.2 | 61% | 39.2 | 112% |

| VCO2 (LPM): | 1.44 | 3.27 | ||

| RER: | 0.88 | 1.09 | ||

| SpO2: | 98% | 97% | ||

| PETCO2: | 37.4 | 34.1 | ||

| Ve/VCO2: | 30 | 34 | ||

| Ve (LPM): | 43.0 | 55% | 110.3 | 142% |

| Vt (L): | 1.64 | 2.57 | ||

| RR: | 26 | 43 | ||

| HR: | 123 | 71% | 171 | 99% |

| O2/Pulse: | 13.3 | 90% | 17.6 | 119% |

[In addition, the Ve-VCO2 slope from rest to AT was 27.5 and from rest to peak exercise was 30.3 both of which are normal, and the chronotropic index was 0.81 which is low normal.]

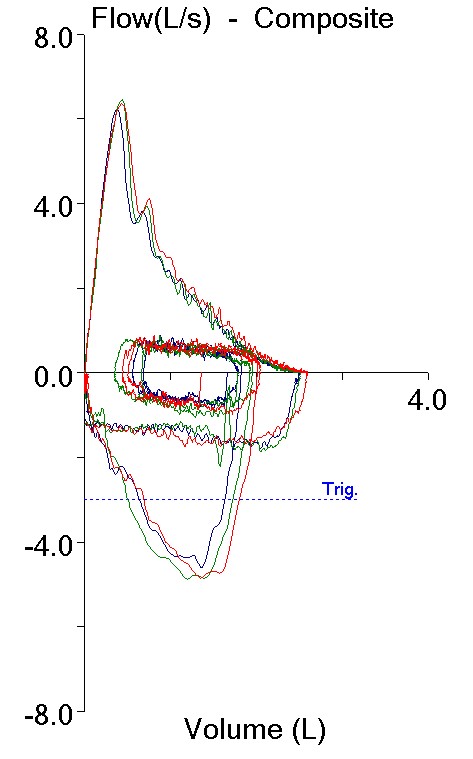

One final point is that we measure Inspiratory Capacity (IC) during a CPET in order to track a patient’s End-Expiratory Lung Volume (EELV). EELV is a surrogate for FRC and we use it to see if a patient is hyperinflating during exercise. This is a common limiting factor for patients with COPD but we routinely measure it on all of our patients (if you don’t look for it you won’t find it!). In this case, not only did this patient’s EELV decrease during exercise by 0.80 L but the maximum IC that was measured during the test was 3.30 L, which is approximately 10% greater than their post-exercise FVC and 27% greater than their pre-exercise FVC.

My take on this patient’s CPET results is that there was a markedly elevated bronchodilation response during exercise. In fact, because we perform post-exercise spirometry at least 10 or 15 minutes following exercise I strongly suspect that this patient’s post-exercise spirometry is significantly underestimating the degree to which they bronchodilated.

So was there a pulmonary mechanical limitation? Since we can’t know for sure how much the patient bronchodilated that question can’t be answered with any certainty. Even using the post-exercise FEV1 x 40, the Ve was 120% of predicted. Usually when we think of an exercise limitation, whether it is pulmonary mechanical, pulmonary vascular or cardiovascular, we are thinking in terms of something that limits or prevents a patient from achieving a normal exercise capacity. When a patient reaches a threshold for one limitation or another but still has a normal maximum oxygen consumption we usually phrase it as the patient “achieved” the limit rather than saying it was an actual limitation. I know that’s just semantics, but how else should it be described?

One final note is that the patient’s main complaint and the reason they weren’t able to go any further was leg fatigue, not shortness of breath. This fact, along with all the others, leads me to suspect that a pulmonary mechanical limit did not in fact occur.

And the low TLC? Some investigators have hypothesized that airway constriction and inflammation occurs heterogeneously in some individuals with asthma. This means that gas trapping occurs patchily all across the lung. During exhalation, these parts of the lung remain inflated and can cause further airway constriction and gas trapping in nearby parts of the lung that are not otherwise involved. This may be the reason that some asthmatics (as many as 10%?) can have a symmetrically decreased FEV1 and FVC with a normal FEV1/FVC ratio during an exacerbation. This patient’s lung volume measurements were performed using helium dilution and it is possible that heterogeneous gas trapping caused their TLC to be underestimated. Having said that there is no reason a patient can’t have both restrictive and obstructive defects simultaneously but if that was the case then this patient’s maximum VO2 of 118% of predicted is even more remarkable.

Is this asthma? In many ways this patient’s clinical course has not been typical and somewhat of a puzzle to their pulmonary physician; hence the CPET. I am not a clinician and my view may be too simplistic, but reactive airways are reactive airways even if the way they react is to bronchodilate rather than bronchoconstrict. A search of the literature indicates that bronchodilation during exercise is not all that unusual, although the degree that it appears to have occurred in this case is exceptionally large. There is a lot of research being performed on the genetics and biochemical pathways of asthma and I suspect that we will eventually find out that what we call asthma is actually just the way that a wide variety of underlying syndromes present themselves. Until that time I think that this just needs to be considered an unusual asthma variant.

Using FEV1 to predict an individual’s maximum minute ventilation does not take into consideration inspiratory flow rates. This is why FEV1 x 40 can underestimate Ve in individuals with severe airway obstruction. FEV1 can also increase during and post-exercise due to bronchodilation. When significant bronchodilation occurs, I have reported CPET results with two predicted Ve’s, one based on the pre-exercise FEV1 and one based on the post-exercise FEV1. Doing this has moved some patients from having an apparent pulmonary mechanical limit to being WNL. In this case, the patient achieved a maximum minute ventilation that was well above either predicted value. Even so I think that this helps make it clear that performing pre- and post-exercise spirometry is important not only to assess EIB but also to detect bronchodilation.

Using FEV1 x 40 to estimate an individual’s maximum minute ventilation is not perfect but it is probably better than any other approach we have at this time. When a patient’s maximum minute ventilation during a CPET exceeds what is predicted for them this can be a sign of poor baseline spirometry (or MVV) test quality or the ability of a compromised patient to slightly exceed expectations. In this case it appears to be a sign of a somewhat unusual asthmatic response to exercise.

References:

ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 211-277.

Gelb AF, Tashkin DP, Epstein JD, Gong H, Zamel N. Exercise-induced bronchodilation in asthma. Chest 1985; 87: 196-201.

Hyatt RE, Cowl CT, Bjoraker JA, Scanlon PD. Conditions associated with an abnormal nonspecific pattern of pulmonary function tests. Chest 2009; 135: 419-424.

Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Stringer WW, Whipp BJ. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation, Fourth Edition, Published by Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2005.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License