My hospital’s Oncology division treats a number of patients with lymphoma and leukemia. It also has an active bone-marrow transplant program and for all of these patients diffusing capacity measurements are a critical part of assessing treatment progress. Since these patients are also frequently anemic, correcting DLCO results for hemoglobin is also critical.

For a factor that has as much importance for the interpretation of DLCO results as it does the effect of hemoglobin on DLCO has actually been studied a relatively small number of times. Part of the reason for this is the problem of finding an acceptable model. A reduced or elevated hemoglobin is a consequence of many diseases and conditions. When studying patients longitudinally it is often difficult to separate the changes in DLCO that occur from the disease process and those that occur from changes in hemoglobin. For this reason changes in hemoglobin pre- and post-treatment in anemia and polycythemia have been studied most frequently.

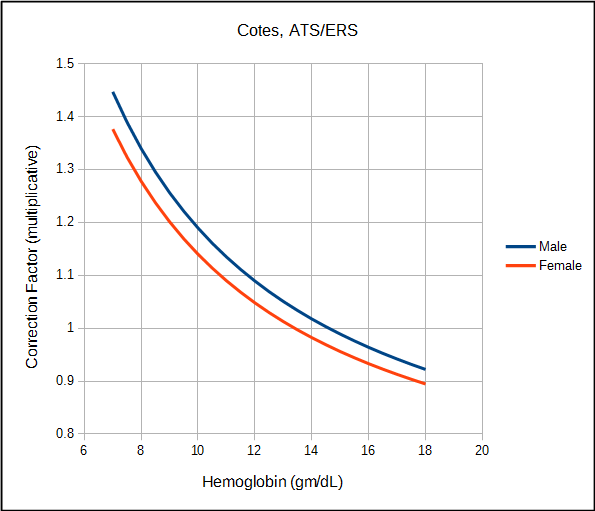

The ATS/ERS currently recommends correcting DLCO for hemoglobin (although notably they recommend that the predicted DLCO be corrected, not the observed value) using the equations developed by Cotes et al in 1972. Cotes’ work was based on subjects with iron-defficienty anemia but just as importantly on theoretical considerations involving Roughton and Forster’s equation on the relationship between the membrane and hemoglobin components of the diffusing capacity:

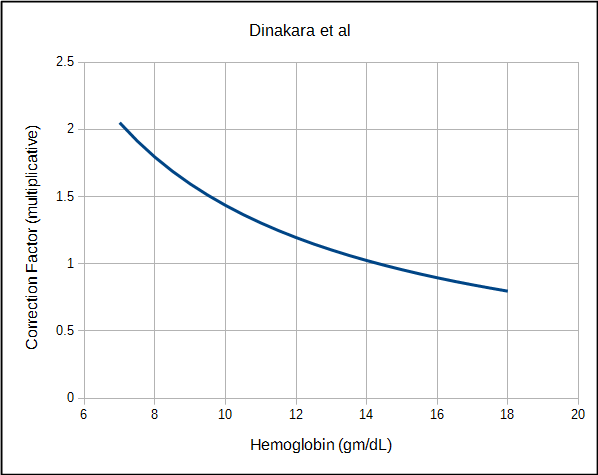

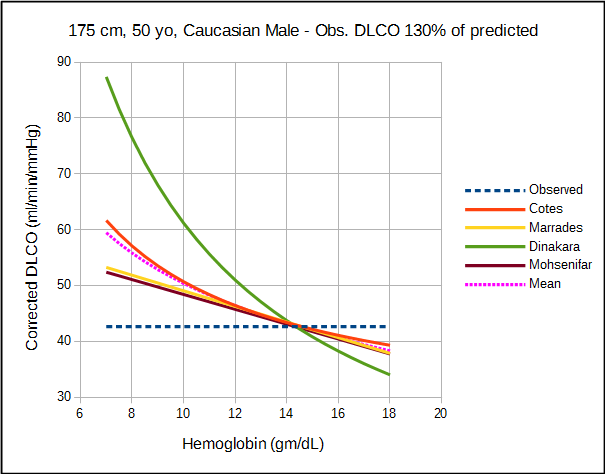

Several other approaches towards correcting DLCO for hemoglobin have been developed. Dinakara et al, studied a group of patients with chronic anemia and found a curvilinear relationship between hemoglobin and DLCO that although generally similar to Cotes, had a significantly greater amplitude.

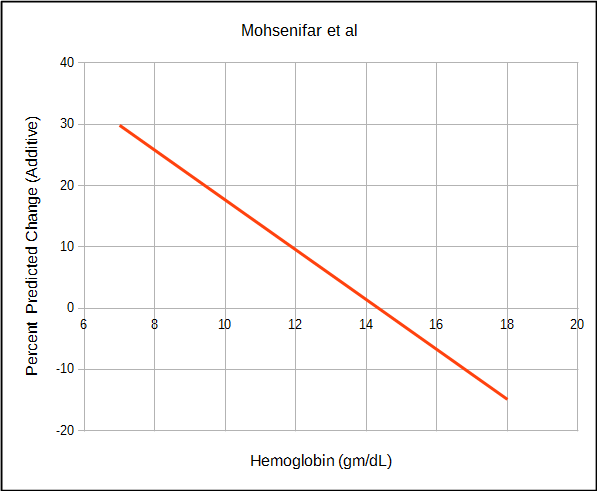

Mohsenifar et al studied a diverse group of patients with anemia or polycythmia as well as normals and instead found a linear relationship between hemoglobin and DLCO.

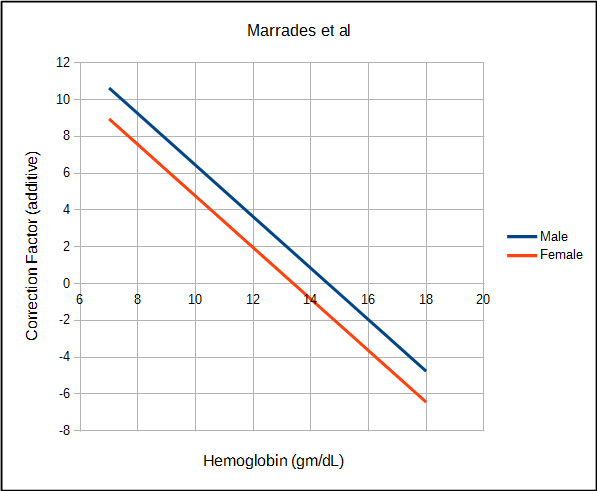

Marrades et al studied a relatively small group of patients with anemia and also found a linear relationship between hemoglobin and DLCO that was quite similar to Mohsenifar.

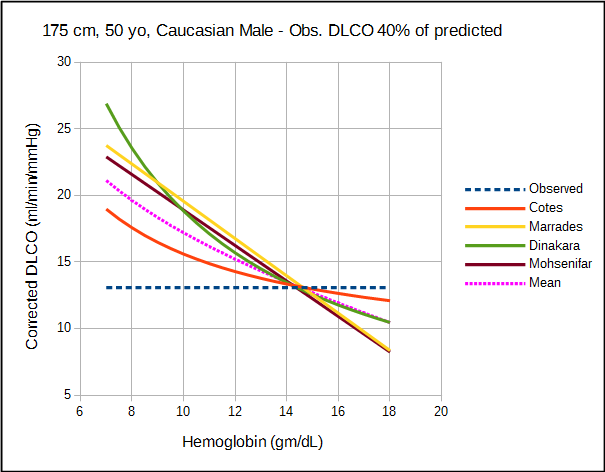

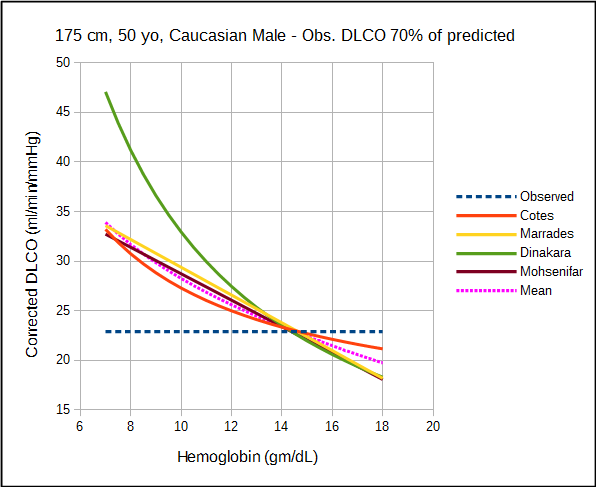

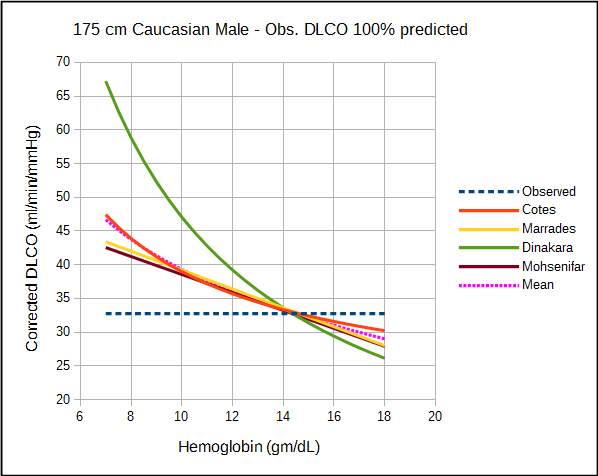

The amount by which each approach corrects DLCO depends variously on the observed DLCO, predicted DLCO, observed hemoglobin and the presumed value for normal hemoglobin. For this reason direct comparison of the correction equations is difficult and must be taken on a case by case basis.

The relatively significant difference in results between studies of what should be a fundamental property of the diffusing capacity makes it difficult to assess the different correction factors. Comparison is also complicated by the fact that DLCO was measured using different breath-holding times (Ogilvie vs Jones-Meade) and FIO2’s (0.21 vs 0.18). Admittedly there is often a fair amount of overlap between correction factors, however which specific factors overlap changes as the observed DLCO and hemoglobin change.

The selection of the Cotes equation by the ATS/ERS is to some extent understandable since it tends to be the most conservative of the correction factors. It’s reliance on the Roughton and Forster equation also makes it the most “scientific” of the correction factors but neither of these reasons necessarily make it the most correct. In particular, the Cotes equation has been criticized because a basic assumption is that the ratio between DMCO (the membrane component of diffusion) and Vc (the capillary blood volume) is a constant of 0.70 over a wide range of DLCO and hemoglobin values.

I found it interesting that the Mohsenifar and Marrades studies generated almost identical correction factors from two different subject groups but I am concerned that the linear relationship that they indicate exists between hemoglobin and DLCO may be too simplistic. Having said that, a comprehensive analysis of CO uptake by red blood cells indicates that DLCO does change linearly with hemoglobin but this observation was based primarily on mathematics and not on empirical data.

Finally, although the Dinakara equation was most often an outlier from the other equations, at least one study has indicated that it more accurately predicted the risk from bone marrow transplantation.

All studies can be criticized to one degree or another for their relatively small subject populations and the lack of a good study model which is unfortunate given how important hemoglobin is to DLCO. For relatively small differences in hemoglobin there is no significant different in the correction factors from the different studies but then same could probably be said of the uncorrected DLCO. At both moderate and extreme differences in DLCO and hemoglobin however, there are significant differences between the correction factors and this has implications for the interpretation of DLCO results.

This is an area that definitely needs more research but it’s far from clear how this should be done. There are reasonably significant physiological differences between acute and chronic anemia (and polycythemia) that make it difficult to develop a reliable human or animal model. In addition the changes in DLCO and hemoglobin that occur due to medications or disease and their treatment are difficult to disentangle. Although there is intriguing evidence that the correction factors developed by Marrades and Mohsenifar may be more accurate than the others, at the present time DLCO should probably continue to be corrected for hemoglobin using the Cotes equation but I say this mostly for the sake of standardization and not because there is any overwhelming evidence that it is the most accurate approach.

| Source: | Gender: | Units: | Formula: |

| Cotes | Male | Ratio | ((1.7 x Hb) / (10.22 + Hb)) |

| Female | Ratio | ((1.7 x Hb) / (9.38 + Hb)) | |

| Dinakara | Both | Ratio | 1 / (0.06965 x Hb) |

| Marrades | Male | DLCO (ml/min/mmHg) | 1.4 x (14.6 – Hb) |

| Female | DLCO (ml/min/mmHg) | 1.4 x (13.4 – Hb) | |

| Mohsenifar | Both | DLCO %predicted | 1.35 x (44 – Hct) |

References:

Brusasco V, Crapo R, Viegi G. ATS/ERS Task Force: Standardisation of lung function testing. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 720-735.

Burgess JH, Bishop JM. Pulmonary diffusing capacity and its subdivisions in polycythemia vera. J Clin Invest 1963; 42(7): 997-1006.

Chakraborty S, Balakotaiah V, Bidani A. Diffusing capacity reexamined: relative roles of diffusion and chemical reaction in red cell uptake of O2, CO, CO2 and NO. J Appl Physiol 2004; 97: 2284-2302.

Coffey DG, Pollyea DA, Myint H, Smith C, Gutman JA. Adjusting DLCO for Hb and its effects on the hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index. Bone Marrow Transplantation 2013; 48: 1253-1256.

Cotes JE, Dabbs JM, Elwood PC et al. Iron-deficiency anaemia: its effect on transfer factor for the lung (diffusing capacity) and ventilation and cardiac frequency during sub-maximal exercise. Clin Sci 1972; 42: 325–335.

Cotes JE, Chinn DJ, Miller MR. Lung Function, Sixth Edition. Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Dinakara P, Johnston RF, Kauffman LA, Solnick PB. Am Rev Resp Dis 1970; 102: 965-969.

Herbert SJ, Weil H, Stuckey WJ, Urner C, Gonzalez E, Ziskind MM. Pulmonary diffusing capacity in polycythemic states before and after phlebotomy. Chest 1965; 48(4): 408-415.

Marrades RM, Diaz O, Roca J, Campistol JM, Torregrosa JV, Barbera JA, Cobos A, Felez MA, Rodriguez-Roisini R. Adjustment of DLCO for hemoglobin concentration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155: 236-241.

Mohsenifar Z, Brown HV, Schnitzer B, Prause JA, Koerner SK. The effect of abnormal levels of hematocrit on the single breath diffusing capacity. Lung 1982; 160: 325-330.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License