Recently I was trying to explain the effect of altitude on blood oxygenation to somebody with IPF. They had observed that their oxygen saturation was fairly normal at sea level but that they needed to use their supplemental O2 when they went up to 2000 feet and didn’t understand why such a low altitude made that much of a difference. I don’t think I did very well with the explanation since at the time I was limited to only text and I much prefer pulling out diagrams and waving my hands in the air.

The place to start is with the alveolar air equation.

Where:

PAO2 = partial pressure of O2 in the alveoli

FiO2 = fractional concentration of O2

PB = barometric pressure

PH20 = partial pressure of water vapor in the alveoli

PaCO2 = partial pressure of CO2 in the arteries

RER = respiratory exchange ratio (VCO2/VO2)

When normal values are plugged into the alveolar air equation it looks like this:

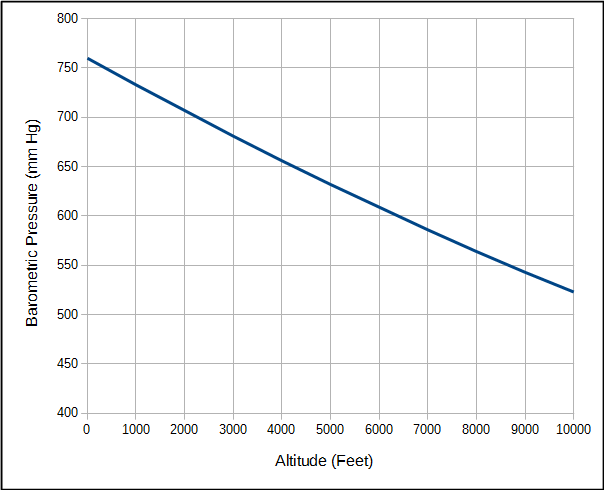

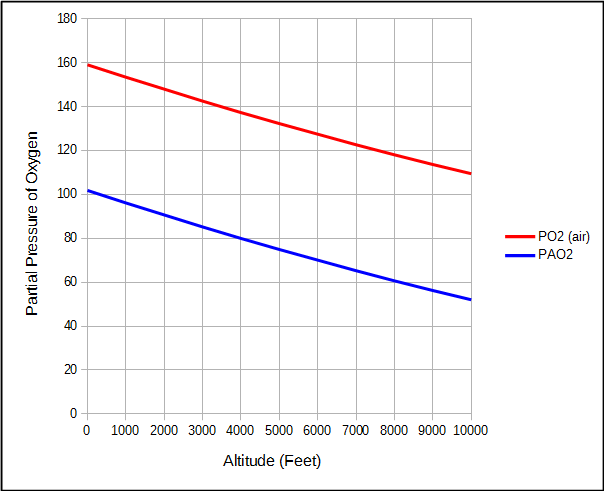

An important point is that when air is inhaled into the lung oxygen is diluted by the water vapor and carbon dioxide that are already there. The partial pressure of oxygen will vary with atmospheric pressure but the partial pressure of water vapor and carbon dioxide are relatively fixed values. Atmospheric pressure of course decreases with altitude.

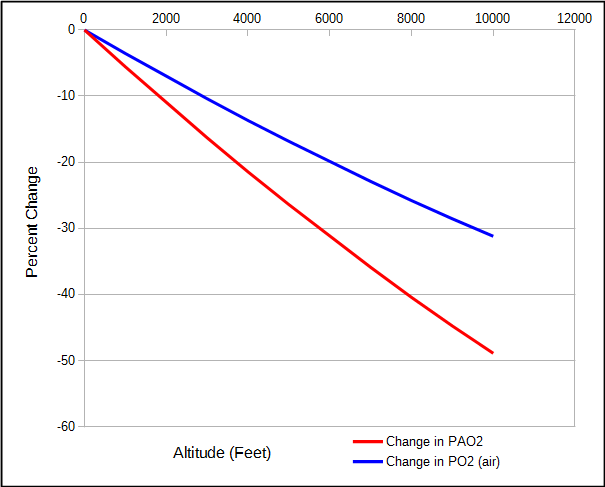

For the same reason, the partial pressure of oxygen in air and the alveoli also decreases as altitude increases.

But because water vapor and carbon dioxide are relatively constant, the partial pressure of alveolar oxygen decreases faster than the partial pressure of O2 in air.

This means that although the atmospheric pressure at 2000 feet is 7% less than at sea level, alveolar PO2 is 11% less.

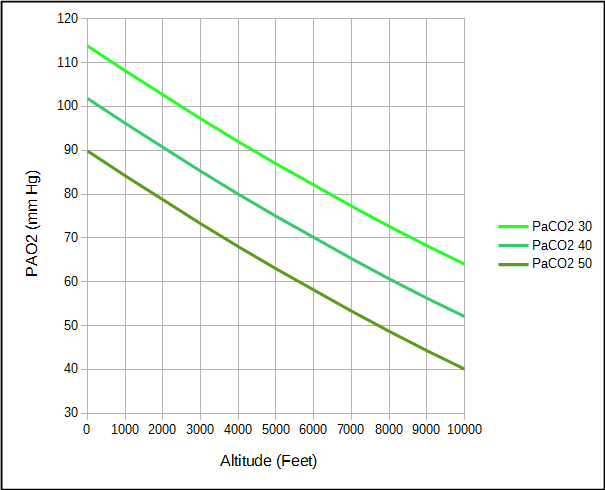

However, not every individual’s arterial PCO2 and respiratory exchange ratio are “normal” and differences can either increase or decrease the alveolar PO2. For example, an elevated PaCO2 decreases PAO2 while a reduced PaCO2 increases PAO2.

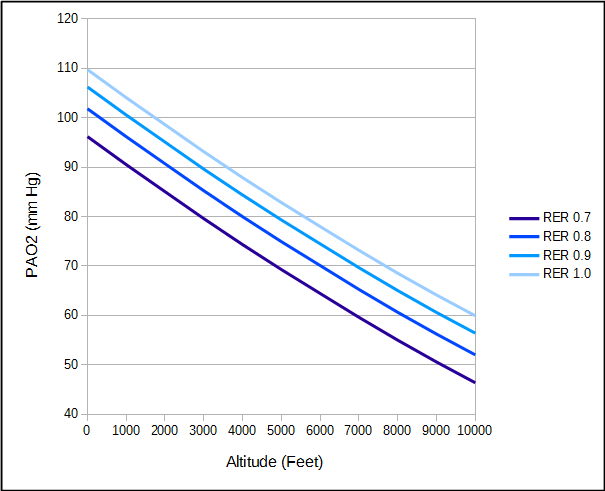

The respiratory exchange ratio is affected both by diet and activity. A high protein diet tends to decrease RER while a high carbohydrate diet or activity tends to increase RER.

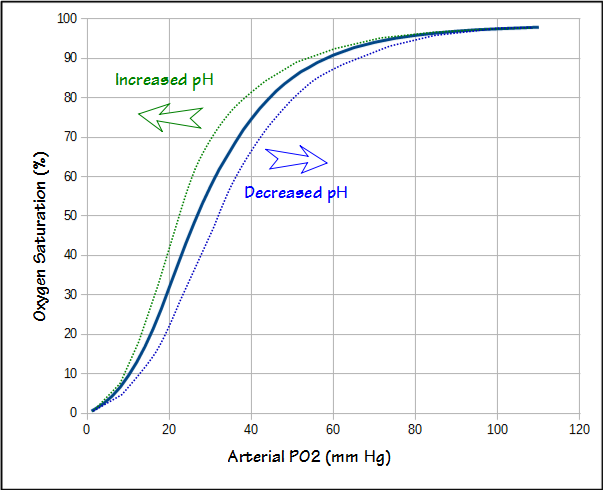

The alveolar air equation only addresses the oxygen concentration in the alveoli. To be of any use oxygen needs to get into the bloodstream. Although diffusing capacity is a measurement of gas exchange efficiency it is not possible to take the DLCO and PAO2, and then predict arterial PO2 (PaO2) with any accuracy. Nor is it possible to measure the arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) with a pulse oximeter and then calculate PaO2. This is because pulse oximeter accuracy is only +/- 3% and blood pH also affects the oxygen dissociation curve.

PaO2 must therefore be measured from an arterial blood sample. When this is done you can calculate the difference between alveolar and arterial PO2 (known alternately as the A-a gradient or PAaO2). The A-a gradient rises with age and at sea level the normal value is approximately:

Results from several studies however, indicate that the A-a gradient decreases with altitude. The decrease is small, only 0.02 mm Hg per mm Hg decrease in atmospheric pressure which is roughly 1 mm Hg per 2000 foot increase in altitude.

Using these formulas and ostensibly normal values for a 60 year old, PAO2, PaO2 and SaO2 would be:

| Altitude (ft): | PAO2: | A-a Gradient: | PaO2: | SaO2: |

| 0 | 101.8 | 19.0 | 82.8 | 96.0% |

| 2000 | 90.7 | 18.0 | 72.7 | 94.6% |

| 4000 | 80.0 | 17.0 | 63.0 | 89.7% |

| 6000 | 70.1 | 16.0 | 54.1 | 87.8% |

| 8000 | 60.7 | 15.0 | 45.7 | 81.5% |

| 10000 | 52.1 | 14.0 | 38.1 | 72.0% |

But the oxygen saturation values at the higher altitudes seem excessively low and this is because one of the adaptations to altitude is an increase in ventilation. This causes PaCO2 to decrease and pH to increase. The decrease in PaCO2 increases PAO2. The increase in pH shifts the oxygen dissociation curve leftwards which means that the SaO2 for a given PaO2 also increases. At 10,000 feet with a PaCO2 of 30 and pH of 7.50 (much more extreme values such as pH of 7.60 and PaCO2 of 20 have been measured in mountain climbers at extreme altitudes), PAO2 would be 64, PaO2 would be 50, and SaO2 would be 92%.

Even a modest change in PaCO2 to 35 without any corresponding change in pH makes a significant change in oxygenation.

| Altitude (ft): | PAO2: | A-a Gradient: | PaO2: | SaO2: |

| 0 | 107.8 | 19.0 | 88.8 | 98.0% |

| 2000 | 96.7 | 18.0 | 78.7 | 95.6% |

| 4000 | 86.0 | 17.0 | 69.0 | 93.8% |

| 6000 | 76.1 | 16.0 | 60.1 | 90.9% |

| 8000 | 66.7 | 15.0 | 51.7 | 86.3% |

| 10000 | 58.0 | 14.0 | 44.0 | 79.6% |

Airplanes that travel at 30,000 to 40,000 feet are usually pressurized to an equivalent altitude of 6000 to 8000 feet and the lower limit of normal for the SaO2 of airplane travelers is usually considered to be between 89% and 91%.

Everybody’s arterial oxygen decreases as altitude increases. The decrease in the availability of oxygen with increasing altitude is due to the decrease in atmospheric pressure but is also influenced by the relatively constant amounts of water vapor and carbon dioxide in the lung. Alveolar O2 therefore decreases faster than would be expected for a simple change in atmospheric pressure. Increased ventilation is a compensatory mechanism that causes changes in PaCO2 and pH and makes oxygen more available. Lung disease tends to decrease the efficiency of gas exchange which increases the A-a gradient and may also limit an individual’s ability to increase ventilation and compensate for hypoxia. For these reasons sometimes only modest changes in altitude are enough to make a significant change in SaO2.

References:

Crapo RO, Jensen RL, Hegewald M, Tashkin DP. Arterial blood gas reference values for sea level and an altitude of 1,400 meters. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160: 1525-1531

Ruppel GL. Manual of pulmonary function testing, 8th edition, 2003.

Vincent J, Hellot MF, Vargas E, Gautier H, Pasquis P, Lefrancois R. Pulmonary gas exchange, diffusing capacity in natives and newcomers at high altitude. Repir Physiol 1978; 34: 219-231.

Wagner PD, Gale GE, Moon RE, Torre-Bueno JR, Stolp BW, Saltzman HA. Pulmonary gas exchange in humans exercising at sea level and simulated altitude. J Appl Physiol 1986; 61: 260-270.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License